Interestingly enough, though utopia meant “nowhere,” it possessed only little currency in the West through much of its history. The fear that utopia might mean something very different than what its advocates desired first appeared in English in 1715 in Thomas Berington’s News from the Dead; or, the Monthly Packet of True Intelligence from the Other World. Written by Mercury. As Bulgarian scholar, V.M. Budokov, has painstakingly and philologically revealed, Berington employed the word seventeen times. In each usage, Berington meant to create a “satiric vision of Britain that inveighs against impiety in contemporary society and views life as a moral nightmare.” The author wanted the reader to associate “Cacotopia” with hell or, perhaps, “worse than hell.” In Cacotopia, the depraved and unethical rule through sacrilege. Though officially atheistic, Cacotopians never cease discussing matters of religion, being obsessed with the topic, [1]but, ultimately, worship something close to Mammon.[2]

If the word cacotopia appeared in print before 1715 or between 1715 and 1818, no scholar has found it. In his utilitarian Plan of Parliamentary Reform, published first in 1817 and then again, revised, a year later, Jeremy Bentham used the term as “the imagined seat of the worst government.”[3] His most important follower and student, John Stuart Mill, used the term again in 1868, claiming “What is commonly called Utopian is something too good to be practicable; but what they appear to favour is too bad to be practicable.” Mill further argued that in place of the term Utopian, one should call them a dys-topian or a cacao-topian.[4] Less frequently, authors also used terms such as “anti-utopians,” “nasty utopia,” or “inverted utopians.”

The term dystopian seems to have remained unused in English until 1952 when two authors, Glenn Negley and J. Max Patrick, believed they were coining the term in their anthology of 33 utopian visions, Quest for Utopia.[5] At this point, regardless of its original usage, dystopian claimed a permanent place (at least, as of 2025) in the English language. Only a decade after Quest for Utopia, Professor Chad Walsh of Beloit College, the man who had introduced C.S. Lewis to Americans in the 1940s, published what must be regarded as the first great study of dystopian literature, From Utopia to Nightmare. Based on a series of lectures from 1959, Walsh’s 1962 book claims that the very change of projected bliss to projected nightmare reveals a fundamental change in the understanding of the human person toward and of his surrounding world. Walsh notes that while man still believed in formulating utopia, he equally understood that such a utopia could never be sustained.[6] Five years later, in 1967’s The Future as Nightmare, Mark Hillegas claimed that the change and shift from utopia to dystopia in the popular mind came with the regimes of Adolf Hitler, Josef Stalin, and Franklin D. Roosevelt.[7]

As of the third decade of the twenty-first century, dystopia has entered the Anglo-American vocabulary with a vengeance. Children’s books, cartoons, and rock bands throw the term around without hesitation. Novels appear frequently employing the concept, as do comic books and graphic novels. Nowhere, though, does dystopia play such a role in current culture as it does in film and on TV. From Blade Runner to Dark City to Batman Begins, and from the X-Files to Firefly to Fringe, dystopias abound on huge and small screens. Some dystopias are clinically clean, while others ooze grit and muck. Perhaps most importantly, dystopias or dystopian elements appear in a variety of genres and arts. While some authors have blatantly employed dystopia as a genre, such as in P.D. James’s The Children of Men(1992) or in the videogame Bioshock (2002), others have employed singular dystopian elements such as Stephen King in The Stand (1978) or Joss Whedon in Firefly (2002). It is these latter ideas that demonstrate the acceptance and prevalence of dystopia as an idea, showing that it can be casually or informally dropped into various arts, recognizable by its varied audiences.

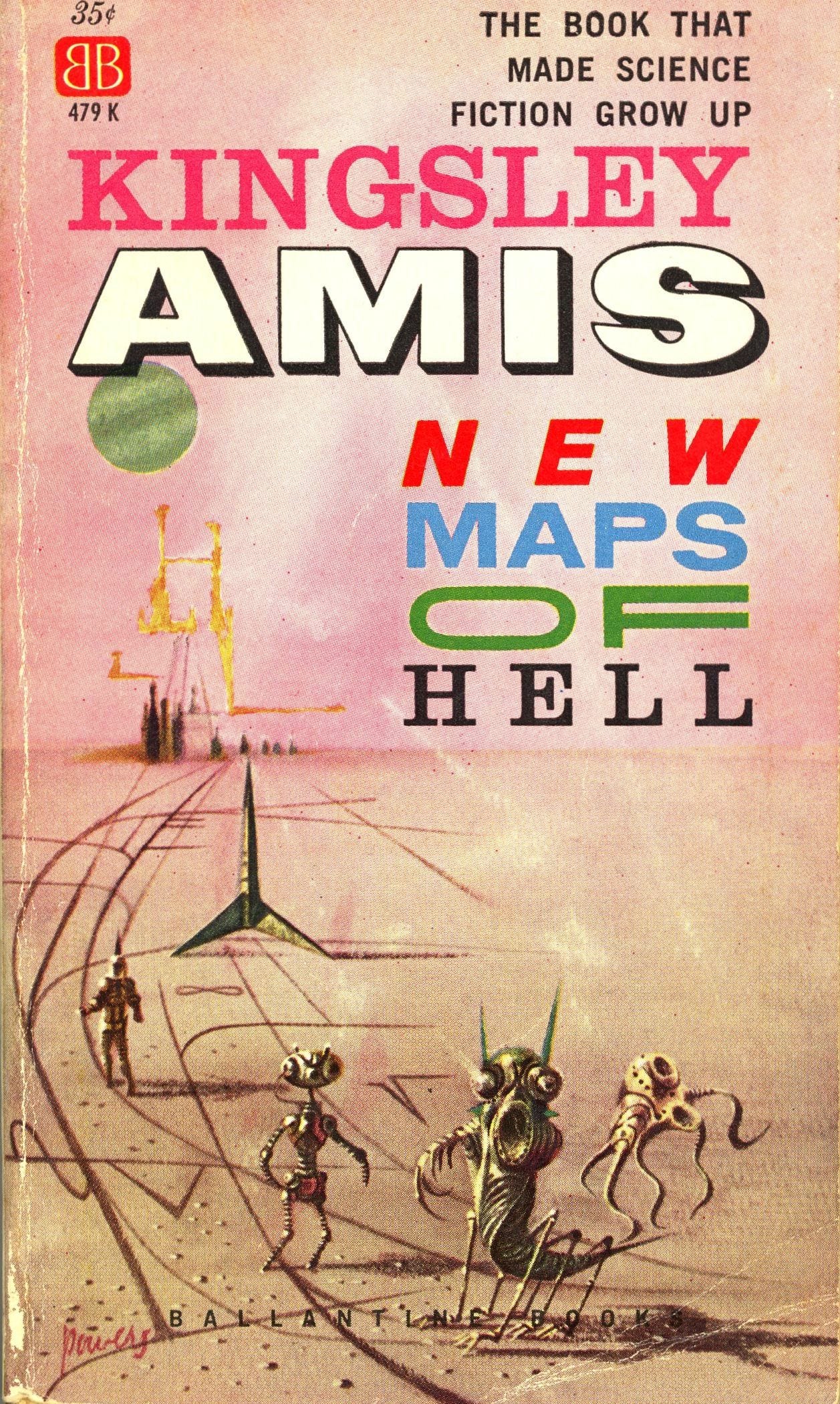

In many ways, dystopian literature legitimized science fiction as a genre. Prior to the 1950s, most viewed science fiction literature—known in the 1930s and 1940s as “scientifiction” or as “pseudoscience fiction”—as nothing more than stories for boys, pulp, often, paradoxically, sold in drug stores and train stations next to quasi-pornographic and sadistic material.[8] With the rise of serious fantastic literature, such as that by Huxley, Lewis, and Orwell, all respected scholars and men of letters, science fiction took on an air of respectability it had never previously enjoyed. “Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, you will be glad to hear, went down very well in science fiction circles, and has been assimilated into the medium, as it were,” Amis claimed.[9] But, even this could not satisfy the critics. Those who admired Huxley, Lewis, and Orwell all claimed the men to be writing creatively, not simply as “science fiction” writers. The same case would later be made for the dystopias of Margaret Atwood and Cormac McCarthy. They only “accidentally” had written science fiction. Even as science fiction became more respectable in the 1950s, though, critics remained adamant it was poor form of literature. Calling those who wrote and read science fiction members of a “cult,” Siegfried Mandel and Peter Fingesten, in the august pages of the Saturday Review, broadly dismissed the genre as simply a “moody discontent with things as they are,” a “magnified claustrophobia.”[10]

The essence of this guide, I hope, will prove the Saturday Review not just wrong, but very, very wrong.

[1] Kingsley Amis, New Maps of Hell (New York: Ballantine, 1960), 66.

[2] V.M. Budakov, “Cacotopia: An Eighteenth-Century Appearance in News from the Dead (1715),” Notes and Queries (2011): 391-394. Budakov’s description of Berington’s use of the term as a false or corrupt Britain seems very close to C.S. Lewis’s contrast between Logres and Britain in That Hideous Strength (1943) as explored later in this book.

[3] The Oxford English Dictionary mistakenly claims Bentham as the neologician behind the term. See “Cacotopia” in OED. A few recent scholars have attempted to resurrect the term “cacotopia,” distinguishing it from dystopia. Cacotopia, they assert, refers to the moral collapse of society while dystopia refers to the political collapse. See, for example, Matthew Beaumont, “Cacotopianism, the Paris Commune, and England’s Anti-Communist Imaginary, 1870-1900,” ELH 73 (Summer 2006): 465-487; and Eric D. Smith, “’A Presage of Horror!’: Cacotopia, the Paris Commune, and Bram Stoker’s Dracula,” Criticism 52 (Winter 2010): 71-90.

[4] Mill quoted in OED, “dystopian.”

[5] Glenn Negley and J. Max Patrick, The Quest for Utopia (New York: Henry Schuman, 1952).

[6] Walsh, From Utopia to Nightmare (London, ENG: Geoffrey Bles, 1962), 16.

[7] Hillegas, The Future as Nightmare: H.G. Wells and the Anti-Utopians (Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 1967).

[8] The best examination of the culture of pulp writing in the 1930s-1950s is Frank Gruber, Pulp Jungle (Los Angeles, CA: Sherbourne Press, 1967). Gruber believed that all writers of “pseudoscience writers were weirdies” (pg. 48). The term, he claimed “was a rather broad one to begin with. It included ‘science’ stories, fantasy, tales of monsters and werewolves” (pg. 49). See also, C.S. Lewis, “On Science Fiction,” in Walter Hooper, ed., Of Other Worlds: Essays and Stories (San Diego, CA: Harcourt Brace), 59-73. Terminology remains contentious. Russell Kirk, for example, happily called all such literature—science fiction, fantasy, dystopian, and apocalyptic—a form of fabulism. See, for example, Kirk, Enemies of the Permanent Things. Tom Shippey, perhaps the greatest living scholar of the genres, has labels it “fabril.” See Shippey, “Introduction,” to The Oxford Book of Science Fiction Stories (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992): ix-x.

[9] Amis, New Maps of Hell, 66.

[10] Siegfried Mandel and Peter Fingesten, “The Myth of Science Fiction,” Saturday Review (August 27, 1955), 7-8. Not surprisingly, many critics of the non-fiction works of Russell Kirk argued the very same about the conservative. He was a man merely discontent with his place in time and space, moody about a lost world that never actually existed.

I appreciate the Bioshock reference. I was playing that game during my undergrad at Hillsdale. It was the first time I saw video games a medium for storytelling.