Remembering Ronald Reagan

And, introducing William Inboden

[Dear Reader, this was an introduction, given on October 28, 2024, at Hillsdale College]

Good evening. On behalf of Hillsdale College and the Center for Military History and Strategy, I would like to welcome everyone.

My name is Bradley Birzer, and I’m now in my twenty-sixth year teaching history at the college. My esteemed colleague, Dean Paul Moreno (also known as the world’ greatest Martini mixer and expert on all things Yankee-baseball) and I arrived in Hillsdale in late July of 1999.

Additionally, my two oldest children recently graduated from Hillsdale (sadly, with degrees in English not history), and my second two children, though, are or will be history majors—one currently a junior and the other a freshman. And, to make things even cooler, my wife, Dedra, also teaches history at the college.

We have deep roots here. I try to remind myself every day I come onto campus that we are one truly great college. Not only do we have the best students and faculty, but we have a long heritage of fighting the good fight. We fought the good fight yesterday, and we fight the good fight today.

I like to think of the Abolitionists who founded this college back in 1844

Who made it color blind from the beginning

Who made it possible for women to earn a liberal arts degree

And, I like to think of the many young Hillsdale men who gave their lives in the Civil War, fighting to protect an enduring republic. I am especially attached to those men in the 24th Michigan who intentionally sacrificed themselves by creating a bottleneck just to the West of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Though greatly outnumbered by the opposition, what remained of the Iron Brigade (and the 24thMichigan) prevented Confederate forces from taking the high ground. Twenty-minutes of immense sacrifice might very well have changed the fate of the world, and, thus, ultimately, the fate of the world.

I can’t help but believe that the liberally educated troops from Hillsdale were inspired by Leonidas and his 300 Spartans at Thermopylae, 23 centuries earlier.

Every time I walk onto campus, I so very much want to live up to what so many have given for us to be here.

So, in every way, getting to offer this brief speech tonight is an honor for me.

An honor to have served for a quarter of a century under the mighty Larry Arnn

An honor to work with outstanding colleagues (who are also serious friends) like Mark Moyar, the director of the Center for Military History and Strategy; Jason Gerkhe, Associate director of the center; and the Rev. Dr. Korey Maas, our department chair.

It’s an honor to speak before we adjourn to Plaster Auditorium to hear our august guest, William Inboden, and. . .

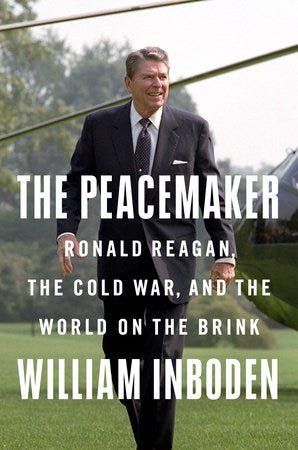

It’s the greatest honor to speak about one of my three favorite presidents, Ronald Reagan.

The Founders did a brilliant job in creating the office of the presidency—no republic had ever had one--but I think we can all admit, it’s not the easiest job. And, I would go so far as to say that though we’ve had men of excellent character such as John Quincy Adams hold the office, we’ve really had only had a few truly outstanding presidents who could mix character and ability. For me, the top three are George Washington, Abraham Lincoln, and Ronald Reagan. In the next tier, I would add Grover Cleveland, Calvin Coolidge, and Dwight D. Eisenhower. We’ve had some truly vile men as presidents as well. Immediately, I think of James Buchanan and Woodrow Wilson.

But, we’re at Hillsdale, and so we need love the good, the true, and the beautiful.

That brings me back to the fortieth president of the United States, Ronald Wilson Reagan. This is the man, after all, who along with Pope John Paul II and Margaret Thatcher, brought down the Soviet Union. And, he did it with conviction and class.

I’ve had the great privilege of reading numerous memoirs about Reagan, and one of my favorites, surprisingly enough, is by the moderate-liberal David Gergen, who served in Reagan’s as well as in Bill Clinton’s administration.

“Reagan wasn’t just comfortable in his own skin. [152] He was serene. And he had a clear sense of what he was trying to accomplish. Those were among his greatest strengths as a leader. Nobody had to tell him those things. He knew where he wanted to go and how he might get there. Instead of trying to treat him like a marionette, as we did sometimes, the best thing was could do on staff was to help clear the obstacles from his path.” [Gergen, Eyewitness to Power, 152-153]

And,

“Working for him, I saw he was no dullard, as his critics claimed. From his eight years as governor and his many other years of writing and speaking out, he had thought his way through most domestic issues and knew how to make a complex governmental structure work in his favor. In the first year of his presidency, I also saw him dive into the details of the federal revenue code and become an authority as he negotiated with Congress. When he wanted to focus, he had keen powers of concentration and could digest large bodies of information. He was also one of the most disciplined men I have seen in the presidency (much more so than Clinton, for example), so that he worked straight through the day, reading papers and checking off meetings on his list. At day’s end, headed off for a workout and would plow through more papers in the evening in the upstairs residence. He made the presidency look easy in part by keeping a strict regimen. He also had a retentive mind. After years of memorizing scripts in Hollywood, he would recall verbatim a lot of what he had read. He recited Robert Service poems as well as he did jokes.” [Gergen, Eyewitness to Power, 197]

I must admit something personal about Reagan, too. He was first elected when I was in seventh grade, and he gave his farewell address my junior year of college. The Berlin Wall fell eight months later as Reagan—and maybe only Reagan—knew that it would.

But, I’m especially reminded of the singular beauty of his Farewell Address, perhaps his greatest articulation of what he thought America could be.

I've spoken of the shining city all my political life, but I don't know if I ever quite communicated what I saw when I said it. But in my mind it was a tall, proud city built on rocks stronger than oceans, wind-swept, God-blessed, and teeming with people of all kinds living in harmony and peace; a city with free ports that hummed with commerce and creativity. And if there had to be city walls, the walls had doors and the doors were open to anyone with the will and the heart to get here. That's how I saw it, and see it still.

And how stands the city on this winter night? More prosperous, more secure, and happier than it was 8 years ago. But more than that: After 200 years, two centuries, she still stands strong and true on the granite ridge, and her glow has held steady no matter what storm. And she's still a beacon, still a magnet for all who must have freedom, for all the pilgrims from all the lost places who are hurtling through the darkness, toward home.

Reagan, it should be remembered, made us great—because he actually believed we were great, that we were better than we knew, braver than we suspected, and more courageous than we thought possible. He brought the best out of us, and made us better than we were.

But, I do want to go back to the beginning of his presidency.

When he took office in January 1981, he really didn’t know what he was doing. He had a mandate from the American people, but he had to get his own staff in order and he had to figure out how to deal with Congress. Aside from Iran releasing the hostages, Reagan didn’t have many victories in those first few months. Then, to the horror of everyone, a young man from Utah tried to assassinate him. He failed, but Reagan somehow became a mythic figure, a man who could do no wrong. Even his enemies admired his strength in recovery.

He wrote in his diary: Whatever happens now I owe my life to God and will try to serve him in every way I can.”

He also wrote that he wished his would-be assassin nothing but good health, praying he would get the help he needed.

Not surprisingly, Reagan made no public appearances in April and early May. His first public appearance, then, was on May 17, 1981. He gave the commencement address at the University of Notre Dame. Amazingly, though I was 13, I was there, as my oldest brother was in that graduating class.

President Reagan considered the speech and the moment so important, he wrote his own speech. Here’s just a bit of it:

We need you. We need your youth. We need your strength. We need your idealism to help us make right that which is wrong. Now, I know that this period of your life, you have been and are critically looking at the mores and customs of the past and questioning their value. Every generation does that. May I suggest, don't discard the time-tested values upon which civilization was built simply because they're old. More important, don't let today's doomcriers and cynics persuade you that the best is past, that from here on it's all downhill. Each generation sees farther than the generation that preceded it because it stands on the shoulders of that generation. . . . .

The years ahead are great ones for this country, for the cause of freedom and the spread of civilization. The West won't contain communism, it will transcend communism. It won't bother to denounce it, it will dismiss it as some bizarre chapter in human history whose last pages are even now being written.

William Faulkner, at a Nobel Prize ceremony some time back, said man ``would not only [merely] endure: he will prevail'' against the modern world because he will return to ``the old verities and truths of the heart.'' And then Faulkner said of man, ``He is immortal because he alone among creatures . . . has a soul, a spirit capable of compassion and sacrifice and endurance.''

One can't say those words -- compassion, sacrifice, and endurance -- without thinking of the irony that one who so exemplifies them, Pope John Paul II, a man of peace and goodness, an inspiration to the world, would be struck by a bullet from a man towards whom he could only feel compassion and love. It was Pope John Paul II who warned in last year's encyclical on mercy and justice against certain economic theories that use the rhetoric of class struggle to justify injustice. He said, ``In the name of an alleged justice the neighbor is sometimes destroyed, killed, deprived of liberty or stripped of fundamental human rights.''

For the West, for America, the time has come to dare to show to the world that our civilized ideas, our traditions, our values, are not -- like the ideology and war machine of totalitarian societies -- just a facade of strength. It is time for the world to know our intellectual and spiritual values are rooted in the source of all strength, a belief in a Supreme Being, and a law higher than our own.

When it's written, history of our time won't dwell long on the hardships of the recent past. But history will ask -- and our answer determine the fate of freedom for a thousand years -- Did a nation borne of hope lose hope? Did a people forged by courage find courage wanting? Did a generation steeled by hard war and a harsh peace forsake honor at the moment of great climactic struggle for the human spirit?”’

That speech was 43 years ago and 99.9 miles to the West of us. I ended up going to Notre Dame as well. I loved it. But, when I think about Ronald Reagan and everything he stood for, I believe that his true spirit resides here on this campus and at this time. I’m so very honored to be here. And, what an honor to have you here.

I have a book, Reagan In His Own Hand, which consists of notes and brief speeches he gave before he entered politics. It's fascinating and impressive to see how good he was at conveying conservative philosophy early on. Despite what the media said, he was a brilliant man.