Tomorrow morning, the Birzer clan heads west for vacation in Kansas, Colorado, and South Dakota. In preparation for our journey, we watched Last of the Mohicans (even though it takes place in upstate New York; it’s still the frontier) and Dances with Wolves (filmed mostly in South Dakota).

Both present incredible stories, and each has a magnificent soundtrack.

But, each also made me wonder something that I’ve been wondering about for my entire professional career. . . why are American Indians so often ignored in American history? With my colleague Miles Smith, I had a chance recently to defend Hillsdale College’s teaching of Reconstruction, 1863-1877. In our teaching, we very much include the Indian Wars as well as the history of the black freedmen. In most college history courses (outside of Hillsdale), though, scholars deal only with the rise of the KKK, etc., and completely ignore the Indians. How can one legitimately teach 1863-1877 and ignore the Indian Wars? Insanity.

Or, even think about our current obsession with race. This week’s Supreme Court decision on Affirmative Action dealt with blacks, Hispanics, Asian Americans, and whites. Or, think about the 1619 Project or Black Lives Matters. What about a 1492 Project or a Red Lives Matters?

If we really want to assign guilt to whites for their conquering of American, why ignore the native peoples? I just don’t get it. Maybe because the Sioux went against the FBI in the early 1970s—and the New Left has always had a soft spot for the FBI? I ask in earnest.

The “Indian Problem”

A few years ago, I was asked to write my thoughts on nineteenth-century American Indian removal and the so-called “Indian Problem,” a difficult and complicated subject, to be sure. Here’s what I wrote:

One of the perennial problems in nineteenth-century American history was the so-called “Indian Problem.” And, a problem it was. American whites either idealized or demonized the Indians, usually depending on how far one lived from native tribes. The natives—understandably—did everything possible to protect their own hearth and homes, and many American reluctantly respected them for this, even while destroying them.

In the icy, winter chill of a December day in 1831, the greatest Frenchman of his age, Alexis de Tocqueville, looked down the snow-packed banks, toward the partially frozen water of the Mississippi River. The European aristocrat--imbued with the ideas of Edmund Burke--looked upon the scene with mixed disgust and pity. Though he had come to America ostensibly to study its prison system, he had instead spent the majority of his time studying his real passion, the functions and trappings of the institutions of the first modern Republic, which he hoped would be the future for humanity. But this, the coerced removal of entire peoples and the denial of all natural rights, represented the negative, repulsive, and contradictory side of American democracy. As he watched the forlorn and destitute Choctaws cross the Mississippi, leaving their nervous and howling dogs behind on the eastern shore for sheer lack of room in their decrepit boats, Alexis de Tocqueville believed “the Indian race [was] doomed to perish.”[i]

While not defending his actions, one can state three things definitively about President Andrew Jackson and Indian Removal. First, he did not believe whites as biological beings were superior to American Indians as biological beings. Jackson did not hold what would later be called a racist or racialist view toward or against the Indian. In true Jeffersonian fashion, he believed them equal physically and in terms of intelligence to any of European ancestry.[1] He did, however, hold that they were far behind in their cultural adaptation, still struggling with hunting and gathering rather than fully embracing agrarian life.

Second, he firmly believed the removal of the Indians far and permanently away from white-American civilization a good for all involved. Even where the Indians had done well and adapted to the next stage of cultural achievement, agrarian society, whites all too frequently stole their land and mistreated them.

It has long been the policy of government to introduce among them the arts of civilization, in the hope of gradually reclaiming them from a wandering life. This policy has, however, been coupled with another wholly incompatible with its success. Professing a desire to civilize and settle them, we have at the same time lost no opportunity to purchase their lands and thrust them farther into the wilderness. By this means they have not only been kept in a wandering state, but been led to look upon us as unjust and indifferent to their fate.[2]

Too many misconceptions existed between the two peoples, and it would be very difficult for either side to overcome these. The history of European-American Indian contact furnished even the least aware mind that conflict had arisen incessantly on the frontier, at the point of contact. Conflict was not the only result, as trade had often flourished and new mixed-blood families had been created. But, by and large, as the Americans became more and more agrarian, taking up more land and cultivating it, demanding the security of the property they worked, they would continue to see the Indian and Indian hunting grounds as barriers to civilization. Removing the American Indians to the area to the west as a “Permanent Indian Frontier” (the 95th meridian, roughly where Kansas City is), Jackson hoped, would take the Indian out of the path of frontier settlement, and it would allow the various Indian cultures and peoples to adapt at their own speed to agricultural life.[3]

As a means of effecting this end I suggest for your consideration the propriety of setting apart an ample district west of the Mississippi, and without the limits of any state or territory now formed, to be guaranteed to the Indian tribes as long as they shall occupy it, each tribe having a distinct control over the portion designated for its use. There they may be secured in the enjoyment of governments of their own choice, subject to no other control from the United States than such as may be necessary to preserve peace on the frontier and between the several tribes. There the benevolent may endeavor to teach them the arts of civilization, and, by promoting union and harmony among them, to raise up an interesting commonwealth, destined to perpetuate the race and to attest the humanity and justice of this government.[4]

Additionally, just as the white European had encountered a more primitive peoples (culturally), now they, the Eastern American Indians, would encounter a less primitive peoples, the horse culture of the Great Plains. Perhaps the new settlers could begin to leaven the culture of the Plains Indians, just as the first European-Americans had done with the Eastern American Indians. All of this seemed pretty nice in theory, and Jackson even diligently wrestled with notions of sovereignty and, especially, sovereignty within sovereignty, as John Marshall and the Supreme Court would as well in the aftermath of this policy. Jackson was able to get his allies, barely, to pass The Indian Removal Act in late May 1830.[5] Jackson considered it a hallmark piece of legislation and a seminal part of his presidency.

The modern historian must also, however, state the third fact about Jackson’s Indian removal policy. It was a disaster at every level, not only to and for American Indian cultures, but to and for the very integrity of the American republic and the U.S. Constitution as well. For the purposes of this biographical essay, we need look no further than the example of Choctaw removal, one of the first southern “civilized” tribes affected by the Indian Removal Act. Amazingly enough, the visiting Alexis De Tocqueville ran into the migrating people, as noted above, on a horrific winter day, December 1831, as they were attempting to cross a partially frozen Mississippi River.

At the end of the year 1831, I found myself on the left bank of the Mississippi, at a place named Memphis by the Europeans. While I was in this place, a numerous troop of Choctaws (the French of Louisiana call them Chactas) came; these savages left their country and tried to pass to the right bank of the Mississippi where they flattered themselves about finding a refuge that the American government had promised them. It was then the heart of winter, and the cold gripped that year with unaccustomed intensity; snow had hardened on the ground, and the river swept along enormous chunks of ice. The Indians led their families with them; they dragged along behind them the wounded, the sick, the newborn children, the elderly about to die. They had neither tents nor wagons, but only a few provisions and weapons. I saw them embark to cross the great river, and this solemn spectacle will never leave my memory. You heard among this assembled crowd neither sobs nor complaints; they kept quiet. Their misfortunes were old and seemed to them without remedy. All the Indians had already entered the vessel that was to carry them; their dogs still remained on the bank; when these animals saw finally that their masters were going away forever, they let out dreadful howls, and throwing themselves at the same time into the icy waters of the Mississippi, they swam after their masters.[6]

For good reason, Tocqueville looked upon the scene with mixed disgust and pity. Though he had come to America ostensibly to study its prison system, he had instead spent the majority of his time studying his real passion, the functions and trappings of the institutions of the first modern Republic, which he hoped would be the future for humanity. But this, the coerced removal of entire peoples and the denial of all natural rights, represented the negative, repulsive, and contradictory side of American democracy.

Before the Choctaw “Trail of Tears,” the 550-mile forced migration from Mississippi to Indian Territory, their population stood at 18,963. Some estimates claim that upwards of 6,000 died during the migrations between 1831 and 1834. The government had offered incentives for those who departed early, but those who came at late as 1834 “forfeited their rations.” In only the first few years of the Choctaw Nation arriving at its designated location in what is now Oklahoma, cholera, malaria, small pox, and influenza eviscerated the population. “We did not visit a house, wigwam, or camp,” wrote a distressed missionary, “where we did not find more or less sickness, and in most instances the whole family were prostrated by disease. Great numbers of them have died.” The sickness hit the children hardest, and child mortality rates soared. The missionaries were unable to report that “births decidedly outnumber the deaths” until 1855. By 1860, the Choctaw population stood at 13,666, a twenty-seven percent decline from 1831.[7]

No one better than Tocqueville understood the meaning of all of this for the American republic and, indeed, for the future reputation of any republic. “The conduct of the Americans of the United States toward the natives radiates, in contrast, the purest love of forms and of legality,” he wrote with no small amount of irony. “Provided that the Indians remain in the savage state, the Americans do not in any way get involved in their affairs and they treat them as independent peoples; they do not allow themselves to occupy their lands without having duly acquired them by means of a contract; and if by chance an Indian nation is no longer able to live in its territory, the Americans take it fraternally by the hand and lead it themselves to die outside of the country of its fathers.” The Spanish behavior toward the Indians, he continued, will always be identified with “monstrous crimes”—the black legend—that involved the destruction of a people, not the leavening. But, the Americans, with their high terms of rights and equality and liberty and Constitution could murder the Indian wantonly and yet avoid the bad name of the Spanish. “The Americans of the United States have achieved this double result with a marvelous ease, calmly, legally, philanthropically, without shedding blood, without violating a single one of the great principles of morality in the eyes of the world. You cannot destroy men while better respecting the laws of humanity,” he concluded. Then, in the margins of his original draft, he added: “This world is, it must be admitted, a sad and ridiculous theater.”[8]

With similar results, the Americans forcibly removed the other so-called civilized tribes of the South, the Chickasaw, Cherokees, Creeks, and Seminoles. Twice, the Cherokees took their case all the way to the Supreme Court, finding a steady ally in the old Federalist and Chief Justice, John Marshall. In 1831’s Cherokee Nation v Georgia, Marshall’s court ruled that the Cherokees constituted a semi-autonomous community, which it defined as a “domestic dependent nation. A year later, in Worcester v Georgia, Marshall’s court again ruled in the favor of the Cherokees, noting that Georgia, as a state, had no jurisdiction over any Indian tribe that was constituted as a “domestic dependent nation.” Whatever the Supreme Court’s decisions, nothing like judicial sovereignty existed in the nineteenth-century and Andrew Jackson and his successor, Martin Van Buren, ignored the court’s rulings. Not until the 1850s would American politicians look upon the American Indians with any kind of real sympathy, but the Civil War would change all of this completely and fundamentally.

[1] On the Jeffersonian view of the American Indian, see Bernard W. Sheehan, Seeds of Extinction: Jeffersonian Philanthropy and the American Indian (University of North Carolina Press, 1973).

[2] Andrew Jackson, Message to Congress, December 8, 1829.

[3] The “Permanent Indian Frontier” was a jagged line of forts running from present-day Minnesota to Louisiana, lasting from 1817 to 1848. Among the forts were Jesup, Washita, Towson, Smith, Gibson, Scott, Leavenworth, Atkinson, and Snelling. The area west of these forts, most Americans believed, was the “Great American Desert,” unsuitable for English-style yeoman agriculture. The Indians, especially those removed from east of the Missouri River, could live there in peace, unharmed by whites, and able to advance culturally, at least as Jeffersonian theory went.

[4] Andrew Jackson, Message to Congress, December 8, 1829. The drafts of this message, with the important contributions by John Eaton and Martin Van Buren, can be found in Papers of Andrew Jackson 7: 601-630.

[5] “The Indian Bill,” Washington National Intelligencer (May 27, 1830).

[6] Alexis De Tocqueville, Democracy in America vol. 2 (4 volume Liberty Fund edition).

[7] See Bradley J. Birzer, "'An appearance of lively industry about the place': Choctaw Economic Success in Indian Territory, 1831-1861," Continuity: A Journal of History 24 (Autumn 2000).

[8] Tocqueville, Democracy in America, vol. 2.

[i] Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America (New York: Harper and Row, 1988), 324-326.

Anyway, it’s a complicated problem, certainly, but we should never ignore what we did to the American Indian or the fact that there exist in America numerous American Indians, reservations, and problems in 2023.

Other Thoughts

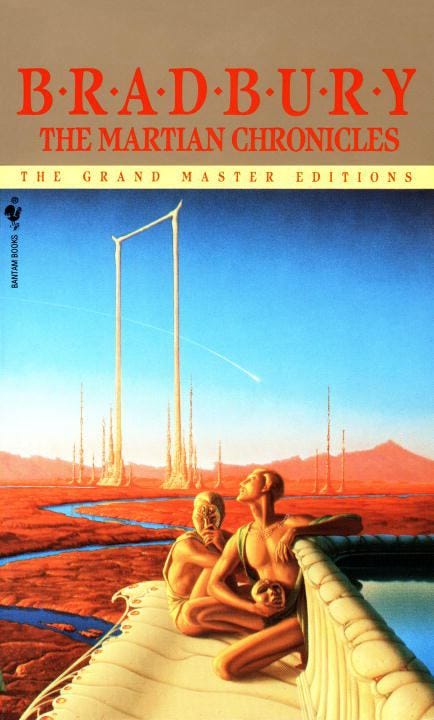

In addition to thinking about the American Indian, I also been reading so much glorious Ray Bradbury (his 1950 Martian Chronicles was a parable about the European invasion of America). I’ll have much more to say about him in future posts.

Thanks for reading this far. Much appreciated, Brad